Souvenir Art

During the 1800s, Americans began traveling more for pleasure. These tourists, as they came to be called, often purchased gifts along the way to take home to loved ones. The “souvenirs,” sometimes marked with a date or name of the destination, became popular collectibles.

Objects:

This silk-sided case might have kept delicate squares of embroidered cotton and linen clean and neat. The embroidery style is particular to the Huron-Wendat, one of the many groups residing in the Great Lakes region. The porcupine quills on this piece are so fine that they resemble moosehair, a common embroidery material. Huron-Wendat artists produced exquisite embroidery on birchbark doll furniture, tea cosies, travel cases, and other goods throughout the 1700s and 1800s.

Case

Unknown Huron-Wendat artist

Wendake, Québéc region, Canada; 1870–1900

Birchbark, silk, dyed porcupine quills

1979.220 Museum purchase

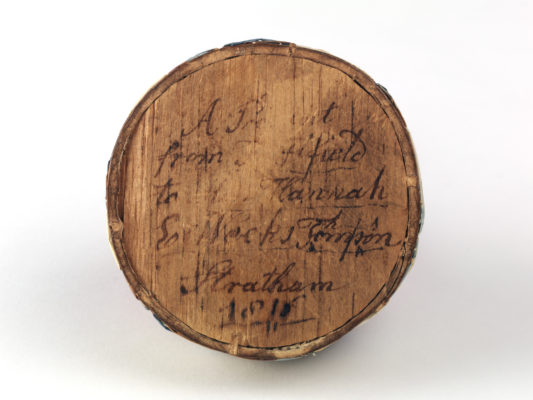

When she was nine years old, Hannah Elinor Weeks Thompson received this box as a gift. It is similar to thousands made by northeastern Native groups for sale to tourists. Hannah, who was born to a wealthy family, married Josiah Bartlett, a well-known New Hampshire doctor, in 1827. Josiah’s great-uncle, Dr. Josiah Bartlett Sr., was a signer of the Declaration of Independence, and the box most likely survives because of that family connection.

Box

Unknown Mi’kmaq artist

Nova Scotia, Canada; before 1816

Wood, birchbark, dyed porcupine quills

1958.1135 Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont

The small, beaded-wool knitting sheath on the left mimics the more expensive and fashionable silver sheath below. Sheaths were fastened to a knitter’s waistband with an attached fabric swatch and helped to hold a needle steady. This wool sheath was made for sale as a tourist souvenir and is a rare survival. Its spare beading pattern indicates that it was possibly made by Wabanaki or Iroquois artisans.

Knitting sheath

Unknown Native American artist

Great Lakes region; 1800s

Wool felt, glass beads, quill

1979.216 Museum purchase

Silver sheaths were extremely valuable, and a young man might give one to his beloved as a courting token. Women often placed advertisements in local newspapers for those that were lost. The silver sheath seen here is inscribed on the front with initials and on the reverse with “October 3d 1849,” which may be the date it was given as a gift.

Knitting sheath

Unknown non-Native artist; 1834

Silver

1959.556 Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont

This wallpocket has suffered a great deal of light damage, and the once-brilliant quillwork decoration has faded from bright blues, reds, and yellows to shades of brown and cream. Native artisans learned to make wallpockets as well as picnic baskets, handkerchief cases, and knitting sheaths specifically for the tourist trade, adapting their traditional techniques to new and profitable forms.

Wallpocket

Unknown Mi’kmaq artist

Nova Scotia, Canada; mid- to late 1800s

Birchbark, porcupine quills, dye

1968.65 Museum purchase

Tourism was big business for eastern Native Americans, even in the early 1900s. The Pequot artisans, like those from other groups, made numerous utilitarian items for sale. Pequot women pounded corn into powder every day for making mush and bread, using large versions of wooden mortars like this one. To decorate their mortars, Pequot artists cut facets into the base with chisels—a design technique unique to the Pequot.

Mortar

Unknown Pequot artist

Eastern Connecticut; 1900–1920

Elm

1979.93 Gift of Mrs. Mary C. Parrish in memory of William Elliot Phelps